Martine remembers the attack vividly.

It was a quiet Sunday in 2019, and her father had just delivered another sermon at his church in Silgadji, a small northern village in Burkina Faso. As the service concluded, the pastor and his flock began exiting the church — only to find themselves surrounded.

The attackers had belts of bullets strapped across their bodies. Metal clanked as they walked. Rifles in hand, the terrorists stormed the Protestant church. “They took the Bibles, the wooden pulpit and threw everything together and burned it all,” Martine recalls.

The terrorists led six men from the congregation to the back of the church, where they forced them to lie on the ground. Then they shot the worshippers — including Martine’s father, husband, brother and brother-in-law — dead.

Martine never saw the violence coming. “There was a good understanding between the Muslims and Christians in our village,” she tells Open Doors, a global network supporting persecuted Christians. “There were no problems between us … Muslims and we loved each other.”

The massacre was among the first attacks on a church in Burkina Faso — a secular state, with a mostly-Muslim population — since it began facing a surge in militant violence, linked to al-Qaida and the so-called Islamic State. Since the insurgency spilled into Burkina Faso’s borders in 2016, hundreds have been killed in extremist attacks on mosques, churches and schools in Burkina Faso.

While Burkina Faso was long seen as a bastion of religious freedom and harmony in West Africa, the emergence of these armed groups means no one in the religiously diverse country is safe from the rising wave of religious violence. And observers agree the government is ill-equipped to stem the tide.

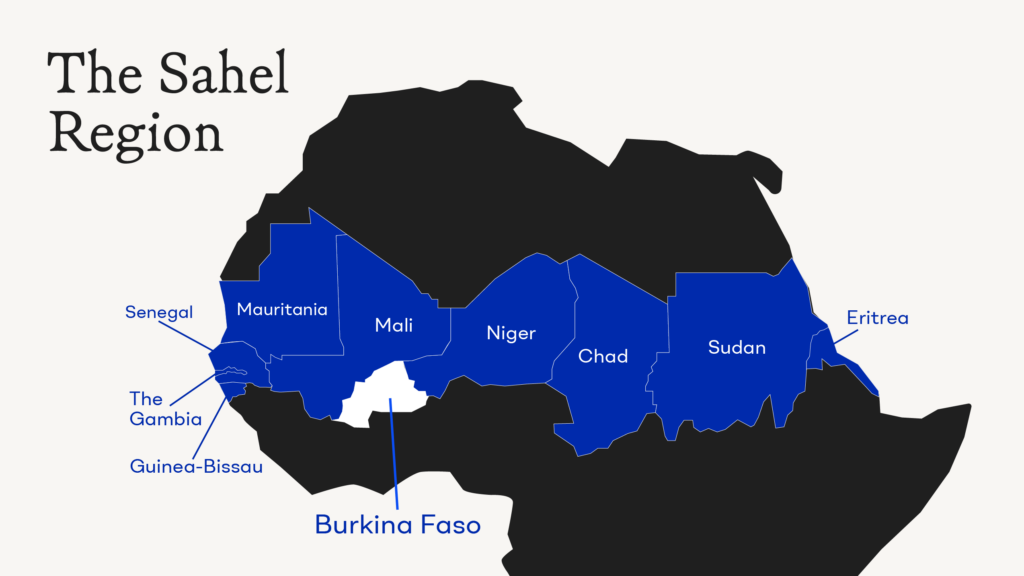

Burkina Faso, locals say, was once a place where Burkinabes — “honest people” — thrived. But the Sahel region — an arid land belt just below the Sahara, stretching from Senegal to Sudan — has seen a seven-fold increase in violence linked to militant religious groups over the past six years, according to the U.S. Africa Center for Strategic Studies’ Africa Security Brief.

“Burkina Faso was known for the peaceful coexistence of different religions, even within families,” says Katrin Langewiesche, who studies religious diversity in Burkina Faso at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. About 61% of Burkinabes are Muslim, mostly Sunni; about a quarter are Christian, mostly Catholic. Another 15% exclusively practice indigenous and animist traditions. That mix of beliefs and traditions, she says, used to be celebrated.

But against the backdrop of unending political instability that resulted in two coups last year, deadly drought that has left over 3 million people facing food insecurity, and armed conflict that has displaced more than 1.4 million Burkinabes, religious violence is only growing.

“Stories about parents and children, spouses, uncles and aunts of different religious affiliations living together are told over and over again, especially today, as if everyone has to convince themselves that it is still possible,” Langewiesche says.

The road to radicalization

Burkina Faso has been on the radar of Frederick Davie, a commissioner for the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), for the last 40 years. He first encountered Thomas Sankara, then the vivacious, energetic president of Burkina Faso, in New York City in the 1980s. Often called “Africa’s Che Guevara,” Sankara had just successfully overthrown the country of Upper Volta, removed its colonial name and renamed it Burkina Faso: “the land of honest men.”

At 33 years old, Sankara attempted to battle corruption and the dominance of former colonial powers. Under his presidency, millions received basic health care for the first time, infant mortality dropped dramatically and women’s rights were expanded.

Though Sankara was assassinated four years into his presidency, Burkina Faso maintained stability under his usurper, Blaise Compaoré. But following Compaoré’s removal in 2014, a power vacuum emerged, and the country began to lose ground against extremist groups.

A landlocked nation, Burkina Faso had thrived even as its neighbors suffered drought, desertification, corruption and ethnic conflict. The country was far from a terrorist hotbed. The United States did not recognize any terrorist organizations in Burkina Faso before 2001, and as recently as 2013, there were no recorded terrorism incidents in the young nation.

About 40% of the country is now under terrorist control, per official figures, with the groups moving rapidly from Burkina Faso’s northeast to its southern and western regions.

The 2011 fall of Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi had direct and dire consequences across the region, according to Open Doors senior analyst Illia Djadi, transforming Libya into a safe haven for terrorists and an arms cache for the region. Weapons stolen from the country were trafficked to rebels in Mali, Burkina Faso’s northern neighbor, where the government has been battling an insurgency since 2012.

Over the past decade, armed groups being pushed from Mali have gained a foothold in Burkina Faso. Government corruption, agricultural issues, simmering ethnic tensions and other humanitarian crises in Burkina Faso created “a cauldron” for growth in militant groups and related violence, Davie adds.

“It’s a real struggle,” he says. “It’s only natural in a situation as volatile as this one that people would look for security, so they become ripe targets” for recruitment to radical groups.

According to the 2023 Global Terrorism Index, last year Burkina Faso saw both the world’s highest number of terrorism-related deaths and the single largest increase in such deaths, jumping from 759 to 1,135. The greater Sahel region saw terrorism deaths climb by more than 2,000% from 2007 to 2022, with Burkina Faso and Mali accounting for nearly three-quarters of those killings.

“One of the factors is [that] national boundaries are very porous,” explains Shobana Shankar, a history professor at New York’s Stony Brook University, whose research focuses on West Africa. “So conflicts that can be locally based, which might have to do with theological or ethnic differences or over resources, become globalized and widened across borders.”

Religion as a weapon

Most of the violence is linked to two Salafi insurgent groups that advanced across the northern border from Mali: the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP), formerly known as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, and the al-Qaida-affiliated coalition Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), which was dubbed last year’s fourth deadliest terrorist group in the Global Terrorism Index.

Analysts believe the rival groups — which have both profited enormously from trafficking drugs, arms and humans over state lines — are ultimately fighting for control over Burkina Faso’s gold mines and trade routes to other regional economic hubs. To win territory, experts say, the insurgents have exploited ethnic tensions as well as grievances against the government for corruption and neglect.

Religious ideology has become a political tool in this crisis, analysts say.

The Sahel has seen reformist Islamic groups in the past, Burkinabe historian Koudbi Kaboré says, though these groups were generally tolerant and peaceful. But the region is now host to “pilgrims, students and traders, with financial resources and degrees that give them social and political influence, [who] have become agents of a Salafist mission that instrumentalizes Islam and communal tensions for political purposes,” he says.

Religious ideology has become a political tool in this crisis.

In the territories they’ve occupied, both ISSP and JNIM have implemented strict forms of religious law based on their extremist interpretations of Islam. The Center for Strategic and International Studies notes that in some JNIM-controlled areas of Mali, terrorists have demanded that civilians accept their governance, relocate or face violence, while ISSP commanders are working to “establish a hardline Salafi-jihadist caliphate in the Sahel.”

Ideological alternatives are not welcome in occupied territories. Churches and other Muslim communities, including Martine’s Protestant community and the Ahmadi Muslim minority, have been targeted for their faith.

Some analysts suggest such targeted violence is less a manifestation of religious intolerance and more of an effort to provoke interreligious conflict. But it’s largely been unsuccessful, Kaboré says. “Although there is mistrust between communities, they avoid falling into the identity trap set by extremist groups,” Kaboré concludes.

No faith is safe

When 15-year-old Aisha Ibrahim rushed to her father’s body on the floor of the mosque’s courtyard, she saw the bullet wound where the 67-year-old imam had been shot and killed. Strewn around him were the bodies of eight other elders from her mosque.

But she held her tears back. “Our elders told me that we do not cry over martyrs,” she says. “Then none of us cried.”

Ibrahim’s father, Imam Alhaj Boureima Bidiga, had been a prominent Wahhabi scholar in the region before 1999, when he joined the Ahmadiyya community, a revivalist Muslim group that is deeply persecuted in many parts of the world. Bidiga then began leading the local Ahmadiyya mosque, situated in Mehdi Abad near the northeastern town of Dori.

That’s where, one Wednesday evening in January, he and about 70 worshippers were gathering for the evening prayer when eight gunmen arrived outside on motorcycles. The militants, suspected to belong to the ISSP, brought eight men into the courtyard along with their imam.

The gunmen urged the worshippers to give up their faith, then made Imam Bidiga an offer: If he renounced his sect, they would spare him. “You can cut off my head, but I cannot leave Ahmadiyyat,” he replied, according to survivors.

All nine men were executed, one after another, in front of their wives and children.

As the gunmen left, they warned the worshippers who remained not to reopen their mosque — otherwise, they threatened, they would return to kill the hundreds of Ahmadi Muslims in the village.

From Kaya to Dori, virtually all of northeastern Burkina Faso is now in the hands of militants, says Mahmood Nasir Saqib, head of the country’s small but growing Ahmadiyya community. “Foreigners can never come as they get kidnapped, and it’s very difficult to travel for the people who live here,” he says. “It’s impossible to come by road or on land as the terrorists have checkpoints. There is a war going on.”

Saqib, who had known the victims and their families for two decades, arranged for the families to be moved to safety in another village. “Lots of Ahmadi Muslims left their houses and took refuge in other places,” he explains. “Ahmadis go into jungles and live there. Conditions are such that we don’t know what will happen.”

Feeding the flames

For two decades, the French and Americans have provided hundreds of millions of dollars to Burkina Faso in humanitarian and military assistance.

But locals and experts agree the effort to beat back the insurgency has not shown any sustained success — and the country’s heavy-handed, securitized approach is only inflaming tensions.

“The military, the security forces in Burkina Faso, they don’t have the capacity to deal with the situations,” says Djadi. “The government is overwhelmed. Even the agencies operating in Burkina Faso are overwhelmed.”

Yet as relations with France and the United States. falter, and many nations divert funds to assist the Ukrainian government and refugees, the flood of Western support may be slowing. The U.S. paused nearly $160 million in aid after last year’s ouster of President Roch Kaboré. In February, French troops — who had begun working with Burkina Faso under the ousted president — pulled out of the country following an order from the new governing junta. Burkina Faso, meanwhile, has shown signs of courting Russian support, making overtures to a Kremlin-linked paramilitary force for assistance.

Humanitarian and religious freedom groups based in the West, including Open Doors and USCIRF, emphasize the need for greater international support. Other analysts and locals blame foreign money and military interference for pushing Burkina Faso to this state.

“The military, the security forces in Burkina Faso, they don’t have the capacity to deal with the situations. The government is overwhelmed. Even the agencies operating in Burkina Faso are overwhelmed.”

“With the phenomenon of terrorism, the superpowers that are fighting over the Sahel have found other virtues” — the fight against terrorism, the protection of locals, the promotion of human rights — “to dress up their strategic ambitions,” Kaboré, the historian, says.

After all, Stephanie Savell of Brown University’s Costs of War project argued in a Foreign Policy op-ed last year, it was the NATO-backed Libyan revolution that took down Gadhafi, helped destabilize Mali and armed extremists across the region.

It was French and American military assistance to keep Mali from falling to terrorists that pushed al-Qaida affiliates to Burkina Faso’s border in the first place, she says, adding that international support enabled Burkina Faso security forces’ and state-sponsored self-defense groups’ widespread human rights abuses, mostly against the country’s disenfranchised Fulani ethnic minority — creating fertile ground for terrorist recruitment of the Fulanis. And, Savell outlines in a 2021 paper, it was the U.S. that laid the groundwork for the notion that the prospect of terrorism in Burkina Faso required a military response.

Instead of using violence to combat violence, some experts tell Analyst News, governments should find solutions to the issues on the ground — such as the widespread poverty, corruption and ethnic divisions that are feeding the militancy.

The U.S. Institute of Peace has argued for a holistic response that addresses the overlapping humanitarian crises, by strengthening social trust and access to education, health care and jobs to reduce the ability for violent extremism to grow. The Center for Strategic and International Studies suggests that military intervention should be “reimagined” to reconcile communities, encourage local ceasefires and focus on local development and protecting civilians. Other observers recommend investment into local anti-extremism initiatives, including youth radio and social media messaging.

Unless the government is able to mount an effective counterterrorism response, the threat that drove Martine’s church and the Ahmadi Muslims from their houses of worship looms over the entire region. The bloodshed in Burkina Faso is spreading even further south, with militant operations crossing the border into neighboring Togo and Benin along the coast.

“This is an existential threat for the whole country,” Djadi says. “If not handled properly, the whole continent will face the consequence.”